Articles: Adoranten 2021

The purpose here is to present, analyze and discuss new observations from the last years’ photogrammetric documentation of the Namforsen’ rock carvings, with emphasis on axe figures, a category that we have previously dealt with some questions still remain to be disentangled (Bertilsson 2019). Results of the documentation accomplished since 2015 raising questions about context and chronology, seemingly more complicated than previously understood. (Bertilsson 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2019, Bertilsson & Bertilsson 2015, 2017, 2018, 2020 and 2021). The 3D models produced enables observations of details and phenomena not previously noticed, making established interpretations less unambiguous and possible to reconsider. First, some comments on recent years’ research on “Northern Hunters Rock Art” (Goldhahn et al. 2010, cf. Bertilsson 2012, Goldhahn 2021).

The concepts Northern and Southern tradition considered to reflect an actual difference between hunter-gatherer’s rock art and farmer’s rock art. The former with northern attributes like single-line ships with moose-headed prows and moose head axes with ears. In this way, the style combined with the geographical location and an assumed chronological significance, is said to confirm that the rock art reflects a cultural form enshrined in its stylistic development.

In Adoranten 2020, folklore material is presented illustrating the beliefs that a potential devastating fire in a magical way could be placed in a sacred stone or boulder. The most interesting example is Dyvelstenen on the Danish island of Samsø (Kaul 2020; Kaul 2021).

In 2021, archive studies, Bornholms Museum, have revealed further evidence as to these ideas of a fire being ‘kept’ in a powerful stone, only released, if the stone was broken or destroyed. In a diary of a local antiquarian, Hans Anker (1858-1923), hitherto unknown information has been found, concerning a fine rock carving stone, covered with more than 100 cup marks, at Ringeby, east of Rønne, Bornholm, Denmark.

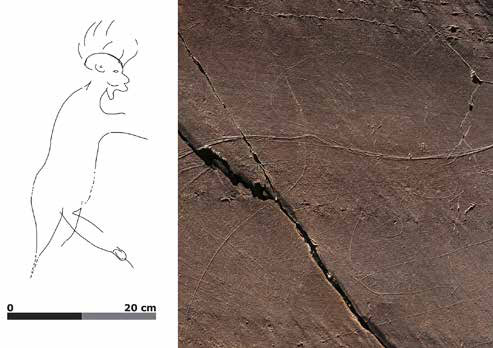

After its dramatic appearance in 1995, with the threat of destruction by a dam counteracted by a worldwide preservation campaign, the open-air rock art in the Côa Valley region fully confirmed the high scientific expectations it raised, with a 30000 yearlong continuous rock art sequence starting in the Upper Paleolithic and up to the Modern Age. It is the world’s largest concentration of Upper Paleolithic open-air rock-art, definitely updating the previously established cave art paradigm within European Paleolithic art. With 20000 years of continuous Paleolithic diachrony, from the Gravettian to the Late Glacial and including the Solutrean and Magdalenian periods, the site of Ribeira de Piscos is among the most important, mainly in the Magdalenian period, where it is the largest and arguably the most prominent site in the region. This text examines some particular figures in this site that display explicit and varied emotional aspects. Besides the scarcity of this trait in Paleolithic art, it can be argued that they played an important role in the establishment and evolution of this site during the Magdalenian, and that this emotional aspect may have been symbolically essential in the definition of the site and its prevalence in the region.

Key words: Rock art; Portugal; Côa Region; Upper Paleolithic; Magdalenian

The long persistence of ancient traditions in India, with the continuance of ritual practices in painted shelters, including handprints, enables us to better understand some of the reasons that may have prompted the authors of handprints in the rock art of the region under study.

Among the sixty-four rock art sites known in the State of Chhattisgarh (India), 750 handprints can be seen on their walls. In seven cases the hands are negative (stencils).

Handprints may also be found in villages on the walls of houses. They are thought to establish a direct relationship between this world and the next. They are perceived by local people as a protection, not as a signature or a casual gesture. Footprints on rock art walls, occasionally associated with handprints, are more rare and have different meanings according to the places where they were made.

If handprint representations are common the world over, in India, and particularly in the region under study, age-old traditions of handprint making are still alive in many places. In certain parts of the State, auspicious prints made on the walls at the house entrance and sometimes on the wall inside the house represent the hands of Lakshmi, the Goddess of Wealth.

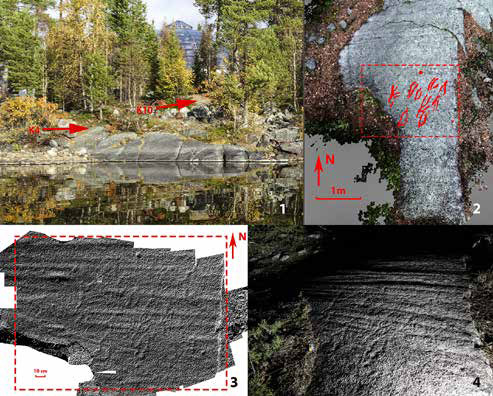

The Kanozero Lake is an overflow of the Umba River located in the southern part of the Kola Peninsula (Murmansk Region, Russia) (Fig. 1) in 26 km distance of the White Sea. First petroglyphs were discovered by Yuri Ivanov in 1997 (Likhachev 1999, Likhachev 2011, Likhachev 2018a). According to the latest catalog (Kolpakov, Shumkin 2012: 16) over 1200 petroglyphs were identified in 18 panels on three islands (Kamenniy Island, Eloviy Island, Goreliy Island) and one “mainland” rocky outcrop (Odinokaya Rock). Between 2016 and 2019, there were discovered five new panels of petroglyphs (Likhachev 2020) and started the process of documenting new figures in known panels including Kamenniy 7 panel (Likhachev 2017) and Eloviy 3 panel (Likhachev 2021b, Kolpakov 2020). According to my data which now still processing the total number of petroglyphs at the Kanozero complex now is more than 1600.

The county Rogaland, in southwestern Norway, has identified 186 rock art sites. The majority are large concentrations of open-air localities in a maritime environment, as well as boulders with carvings. In addition, one rock painting site has been registered in Rogaland (Høgestøl et al. 2018).

In 1995, the Directorate for Cultural Heritage prepared a status report, “Plan for Measures to be Taken to Preserve Rock Art”. The report concluded that approximately 92% of the Norwegian’s rock art sites have major damages (Directorate for Cultural Heritage 1995). Based on this report, the Ministry of the Environment allocated funds for a national project for the conservation and safeguarding of Norwegian rock art. The Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage’s national project formally started in 1996, it was called Protection of Rock Art – The Rock Art Project (Hygen 2006). The aims of the project plan included condition and damage registration, documentation, preservation, and management strategies (Hygen 2006). The Norwegian University museums have continued their work with rock art until today (Kjeldsen 2012).

This article explores how the practice of including rock art in burials from the Bronze Age in Scandinavia was influenced by and incorporated into the new ideas and practices brought about by the introduction of cremation. Three portable stones with rock art found on the exterior of a cairn at the Late Bronze Age site of Sandbrauta in Central Norway are the point of departure for the discussion. Clay from a Late Bronze Age landslide that occurred soon after the ritual activity had sealed off the site, thus revealing the stones with the petroglyphs to be part of the ritual context. It is argued that the stones with rock art displaying different stages of decoration reflect stages in the stones` biography as well as stages in the process of bodily transformation, thus rendering the cairn to be a place for integrated rites involving both the transformation of bodies and rock art.

Keywords: Portable rock art, superimposition, burials, deposition, Central Norway.

|