Articles: Adoranten 2022

During an excavation of a settlement at the edge of a former lake in the bog Ageröds mosse, central Scania, southernmost part of Sweden, a strange object with a handle-hole was found in the refuse. By the date of the deposit where the object was found, it is approximately 9000 years old and belongs to the Late Maglemose Culture. The object of antler has a shape and decoration that is unique to the Mesolithic. It is shaped with a lower ridge in the middle and a shelf near the point. The most obvious motif is a large spiral made of small impressions. On both sides, a curved zigzag made in several rows of impressions can be identified. The best parallel is found on stone pickaxes from western Sweden and western Norway. The spiral is also found on rock carvings in western Norway, which makes the Ageröd object’s origin from that region most likely. In contrast to the most realistic paintings and carvings found during the later Ice Age cultures in southern Europe, the decorations during the ensuing period among hunter-gatherers, the Mesolithic (ca. 9000–4000 cal. BCE) consist of geometric motifs that for us today can almost be described as abstract (Plonka 2003). They occur throughout Europe, but since they are mainly coated as carvings on antler and bone tools, most are found in southern Scandinavia, where the conservation environment for organic material is particularly favorable for this type of material remains.

In the last decade, extensive research in various areas of the central Valcamonica (Capo di Ponte, Nadro di Ceto and Paspardo) has brought to light an immense treasure of rock art (Cittadini 2017; Marretta 2018; Medici & Gavaldo 2019; Rondini & Marretta 2021). Systematic fieldwork, focused here only on the western sites, is reaching an important milestone in the Seradina and Bedolina areas, two important parts of Unesco Site No. 94, where full documentation and analysis of all identified carved panels is rapidly becoming a reality. At the same time, new discoveries of rock carvings not only within the main sites, but also in neighbouring and still little explored areas, significantly increase the density and territorial extent of the carved panels made here in prehistoric times and, as we shall see, contribute to the clarification of old or still unsolved problems. Finally, the now solid data on the distribution of motifs increasingly support the recent hypothesis that certain features of rock art in the western and eastern areas reflect a highly localized phenomenon that remains to be explained in terms of causes and evolution (Sansoni 2016).

Although the relationship between rock art and other evidence of human presence in the territory—such as settlements, cult sites or necropolises—is still weak, new interesting data are also coming from this fundamental area.

Rock art in Britain is typically carved on boulders and outcrops in the open landscape in northern parts of the country. The precise chronology of the carvings is uncertain, but they are generally thought to have been created and used during the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age (c.4000-1800 BC). Carved stones and fragments of carved rock outcrops were occasionally incorporated into Neolithic and Bronze Age ritual structures, including funerary and standing stone monuments, and this practice appears to have been deliberate. Although carved stones are subsequently reused in a range of later structures, these relationships are considered coincidental and lacking in meaning. This article discusses the nature of reuse in the British Iron Age (c.800 BC-AD 100 in England and Wales, and 800 BC-AD 400 in Scotland), and suggests that rock art may have been intentionally built into certain Iron Age monuments in ways that were significant and meaningful.

Britain has a wealth of prehistoric rock art, amounting to over 6,500 carved rocks (or ‘panels’) and thousands of individual motifs, concentrated mainly across Northern England and Scotland. The carvings form part of a wider Atlantic tradition, often termed Atlantic Rock Art, documented in the island of Ireland, Wales, Portugal, and north-west Spain. Similar prehistoric motifs also occur elsewhere in Europe, notably southern Scandinavia, Denmark and Alpine regions.

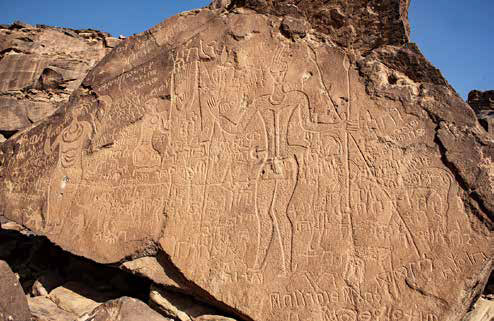

The deserts of Saudi Arabia are exceptionally rich in rock art, mainly in engraved petroglyphs. During the last nine millennia the desert landscapes experienced several climate fluctuations while the general trend went from a modestly moist climate to the present hyper- arid one. Human populations adapted to the corresponding changes in fauna and flora by following different types of economies; several of these changes are mirrored in rock art. A distinctive feature of Saudi Arabian rock art from the first millennium BCE onward is its close association with inscriptions written in at least 15 different scripts, of which the majority were local developments. Whereas most of these inscriptions are brief epigrams, a few of them are highly important official records that shed light on Arabia’s pre-Islamic history. The author recently explored and documented Saudi Arabian rock art. The desert societies of Inner Arabia are often considered unchanging and timeless. However, an analysis of rock art up to ca. 9,000 years old reveals flexible adaptations in economy and social organisation to dramatic climatic and environmental changes. Some economic innovations were adopted from the Levant or Assyria; others developed within Arabia itself.

Scandinavian Bronze Age rock art (1700- 500 BC) is world famous, and has stimulated research for almost 200 years. The rock art shows information about Bronze Age ideology, religion, society, long distance connections, means of transportation, warfare, and hunting by depictions of boats, wagons, weapons, humans, animals and various ritual features. Current research on these images is highly relevant to concerns about society today, providing some of the best evidence for the emergence of social complexity, organized conflict, rituals, and social inequality. The reports in the series Documentation and Registration of Rock Art in Tanum, produced by Tanums Hällristnings Museum Underslös (THU) have been central sources for rock art research. The last 20 years have seen an explosive increase in the number of articles dealing with Scandinavian rock art. A large number of national and international doctoral dissertations and monographs on Bronze Age rock art have also been published. The Swedish Rock Art Research Archives (SHFA) played a crucial role in increasing the momentum of this new wave of academic work and public interest in the rock art. Before the SHFA was founded in 2007, research was long hampered by a lack of access to original documentation.

Focus in this preface is not the field documentation of rock art, rather it discusses what happens to the documents over time, when completed. This discussion connects to a culture of documentation, which has a long tradition, not least, in Scandinavia. Documents become a part of a tradition of memory and reference, which is contiguous and to some degree borderless, and in our days open and accessible to a general public. At the earliest, the handling of antiquarian documentations, was emulating and royal ecclesiastical routines to keep accounts, law texts, diplomatic agreements and commands in an orderly manner. The archives thereby formed, were seen as parts of the sovereign’s and church’s body and could be packed for journeys and transfers between residences. In the manner of the Renaissance it is evident that a new view of the Royal archives is developing through reflecting attitudes of where records could be kept, their handling, order and control. It is possible to have a presentiment of a science of archives to come.

In 2003-2005 excavations were carried out at Madsebakke, a large rock carving field on North Bornholm, Denmark, with Late Bronze Age ship images. The excavation revealed that many activities had taken place here during millennia, from the Early Neolithic to the Late Iron Age. The creation of the rock carvings marks only one line of events related to the Madsebakke out¬crop. Much of the activity at Madsebakke belongs to the Late Bronze Age (1100-500 BC). We shall focus on the finds from an originally large, nearly rectangular, natural depression in the Madsebakke rock, meas¬uring c. 3 x 1 meter, with a depth of about 1 meter. In the Late Bronze Age, many pieces of burnt clay were deposited in the depres¬sion, undoubtedly being wattle of daub, representing burnt buildings. The deposition of burnt clay is not limited to the Madsebakke outcrop. Ex¬cavations at other rock carving sites from Norway and Sweden have revealed similar evidence of depositions of burnt clay, as at Madsebakke often ‘in’ the rock, in cracks and hollows. It seems difficult to explain this recuring phenomenon, where burnt ma¬terial was deposited deliberately.

This paper analyzes a scene from the Kamenniy 7 panel of the Kanozero petroglyph complex (North-West Russia). It could be called a “Bow Elk Hunt” scene. Previously, it was not distinguished as a scene. The article presents arguments in favor of the compositional connection of this scene with the neighboring large composition “Bear Hunt”. The typological similarity of the analyzed scene with another elk hunting scene from this cluster was also revealed. The figure of an elk hunt with a bow is compared with similar scenes from Alta (Norway) and Zalavruga (Karelia, Russia). The petroglyphs of Kanozero, discovered in 1997, are the largest complex of rock carvings on the Kola Peninsula (Kolpakov, Shumkin 2012; Likhachev 2011; Likhachev 2018) (Fig. 1.I.). The largest panel with petroglyphs - Kamenniy 7 - was discovered on the Kamenniy Island in June 1999 (Likhachev 2018: 66) (Fig. 1.III) and, according to the author of the article, contains about 800 figures. Recently, some images and compositions of this panel were documented with use of the photogrammetry technique, which made it possible to see previously elusive image details (Likhachev 2017) . Key words: Kanozero, petroglyphs, Fennoscandia, rock art, narrative, hunting, archer, arrows, elk.

|