Articles: Adoranten 2015

A Stone Age rock art map at Nämforsen, Northern Sweden by Jan Magne Gjerde

The forceful Nämforsen rapids and its landscape have fascinated people for thousands of years. People left their marks on the rocks and numerous settlements in the area. Nämforsen is a unique remnant of the Stone Age where one can sit down on the islands with rock art – close your eyes and travel back in time accompanied by the forceful power and sound of the rapids. Over the past years, I have appreciated numerous visits to this large concentration of rock art in Northern Sweden with more than 2000 rock carvings.

The forceful Nämforsen rapids and its landscape have fascinated people for thousands of years. People left their marks on the rocks and numerous settlements in the area. Nämforsen is a unique remnant of the Stone Age where one can sit down on the islands with rock art – close your eyes and travel back in time accompanied by the forceful power and sound of the rapids. Over the past years, I have appreciated numerous visits to this large concentration of rock art in Northern Sweden with more than 2000 rock carvings.

The forceful Nämforsen rapids and its landscape have fascinated people for thousands of years. People left their marks on the rocks and numerous settlements in the area. Nämforsen is a unique remnant of the Stone Age where one can sit down on the islands with rock art – close your eyes and travel back in time accompanied by the forceful power and sound of the rapids. Over the past years, I have appreciated numerous visits to this large concentration of rock art in Northern Sweden with more than 2000 rock carvings.

The forceful Nämforsen rapids and its landscape have fascinated people for thousands of years. People left their marks on the rocks and numerous settlements in the area. Nämforsen is a unique remnant of the Stone Age where one can sit down on the islands with rock art – close your eyes and travel back in time accompanied by the forceful power and sound of the rapids. Over the past years, I have appreciated numerous visits to this large concentration of rock art in Northern Sweden with more than 2000 rock carvings.

Cupmarks by Christian Horn

A monumental menhir stands upright in front of a circle of stones in Süderbarup, Kr. Schleswig-Flensburg, Schleswig-Holstein. Both, the landscape and the stones are lightly dusted with snow. Forty-five spherical cavities cover the menhir’s rocky surface. In the back, an opening in the surrounding shrubbery grants a view across a greyishwhite winter landscape. Icy forests stretch into the horizon and disappear in the fog. The bluish hue of the scene underscores the forlorn atmosphere. The menhir, known as the ‘guardian stone’, belongs to a Late Bronze burial mound (Groht et al., 2013:470–471).

A monumental menhir stands upright in front of a circle of stones in Süderbarup, Kr. Schleswig-Flensburg, Schleswig-Holstein. Both, the landscape and the stones are lightly dusted with snow. Forty-five spherical cavities cover the menhir’s rocky surface. In the back, an opening in the surrounding shrubbery grants a view across a greyishwhite winter landscape. Icy forests stretch into the horizon and disappear in the fog. The bluish hue of the scene underscores the forlorn atmosphere. The menhir, known as the ‘guardian stone’, belongs to a Late Bronze burial mound (Groht et al., 2013:470–471).

A monumental menhir stands upright in front of a circle of stones in Süderbarup, Kr. Schleswig-Flensburg, Schleswig-Holstein. Both, the landscape and the stones are lightly dusted with snow. Forty-five spherical cavities cover the menhir’s rocky surface. In the back, an opening in the surrounding shrubbery grants a view across a greyishwhite winter landscape. Icy forests stretch into the horizon and disappear in the fog. The bluish hue of the scene underscores the forlorn atmosphere. The menhir, known as the ‘guardian stone’, belongs to a Late Bronze burial mound (Groht et al., 2013:470–471).

A monumental menhir stands upright in front of a circle of stones in Süderbarup, Kr. Schleswig-Flensburg, Schleswig-Holstein. Both, the landscape and the stones are lightly dusted with snow. Forty-five spherical cavities cover the menhir’s rocky surface. In the back, an opening in the surrounding shrubbery grants a view across a greyishwhite winter landscape. Icy forests stretch into the horizon and disappear in the fog. The bluish hue of the scene underscores the forlorn atmosphere. The menhir, known as the ‘guardian stone’, belongs to a Late Bronze burial mound (Groht et al., 2013:470–471).Exaggeration is the message by Rauno Lauhakangas

Sometimes in rock art there are patterns that can be interpreted as a message or as emphasizing a certain activity. This article focuses on one such petroglyph in the Republic of Karelia in Russia. It was engraved 6,700 years ago on the shore of Vyg River, which flows into the White Sea.

Sometimes in rock art there are patterns that can be interpreted as a message or as emphasizing a certain activity. This article focuses on one such petroglyph in the Republic of Karelia in Russia. It was engraved 6,700 years ago on the shore of Vyg River, which flows into the White Sea.

The echo of whales in Karelian petroglyphs I am lying on lichen-covered rock on the shore of the dried Vyg River. My fingers are probing the surface of the rock under the lichen. I am looking for the edge of a petroglyph. Why am I here of all places? The simple answer is that my interest in ancient rock art has brought me here. I know that the Soviet researcher Vladislav Ravdonikas (1938) went to Vyg River in 1932 and made rubbing copies of several petroglyphs. The river flows to the White Sea near the town of Belomorsk, previously called Soroka. The petroglyphs are about 8 kilometers away from the mouth of the river. However, the most immediate reason for my trip is also related to whales and music.

Sometimes in rock art there are patterns that can be interpreted as a message or as emphasizing a certain activity. This article focuses on one such petroglyph in the Republic of Karelia in Russia. It was engraved 6,700 years ago on the shore of Vyg River, which flows into the White Sea.

Sometimes in rock art there are patterns that can be interpreted as a message or as emphasizing a certain activity. This article focuses on one such petroglyph in the Republic of Karelia in Russia. It was engraved 6,700 years ago on the shore of Vyg River, which flows into the White Sea.The echo of whales in Karelian petroglyphs I am lying on lichen-covered rock on the shore of the dried Vyg River. My fingers are probing the surface of the rock under the lichen. I am looking for the edge of a petroglyph. Why am I here of all places? The simple answer is that my interest in ancient rock art has brought me here. I know that the Soviet researcher Vladislav Ravdonikas (1938) went to Vyg River in 1932 and made rubbing copies of several petroglyphs. The river flows to the White Sea near the town of Belomorsk, previously called Soroka. The petroglyphs are about 8 kilometers away from the mouth of the river. However, the most immediate reason for my trip is also related to whales and music.

Making sense of the relationship between water and monument by George Nash

The Kilmartin Valley (also known as Kilmartin Glen) is located within the county of Argyll in western Scotland and covers an area of approximately 50 km2 (11 [north-south] x 5 [eastwest] km). It has within its curtilage one of the largest and most complex later prehistoric landscapes in northern Britain. Monuments include Neolithic and Early Bronze Age (EBA) stone chambered burial ritual monuments (including long cairns, round cairns, barrows and cists), a henge, standing stones and engraved open-air rock art. The Royal Commission for Ancient and Historic Monuments for Scotland (RCAHMS) list over 150 later prehistoric sites within a nine kilometre radius. Engraved rock art is found on or close to burial monuments and as open-air sites on exposed rock outcropping.

The Kilmartin Valley (also known as Kilmartin Glen) is located within the county of Argyll in western Scotland and covers an area of approximately 50 km2 (11 [north-south] x 5 [eastwest] km). It has within its curtilage one of the largest and most complex later prehistoric landscapes in northern Britain. Monuments include Neolithic and Early Bronze Age (EBA) stone chambered burial ritual monuments (including long cairns, round cairns, barrows and cists), a henge, standing stones and engraved open-air rock art. The Royal Commission for Ancient and Historic Monuments for Scotland (RCAHMS) list over 150 later prehistoric sites within a nine kilometre radius. Engraved rock art is found on or close to burial monuments and as open-air sites on exposed rock outcropping.

In 2013, a team of archaeologists from the Welsh Rock Art Organisation (WRAO) began a study on the Later Prehistoric sites that contained rock art in western and northern Britain. This study followed an earlier research project which concentrated on a corpus of open-air sites. One of the areas included within this study was Kilmartin Valley.

This paper assesses and discusses some of the findings of this project, suggesting that rock art provided a ritual link between monument and landscape. The focus of this paper will be the small but significant assemblage of the Neolithic stone chambered monuments, cists and standings stones that occupy the lower, central and upper sections of the valley, extending from the village of Kilmartin and the rugged foothills in the north to the marsh grassland of Mòine Mhòr in the south.

The Kilmartin Valley (also known as Kilmartin Glen) is located within the county of Argyll in western Scotland and covers an area of approximately 50 km2 (11 [north-south] x 5 [eastwest] km). It has within its curtilage one of the largest and most complex later prehistoric landscapes in northern Britain. Monuments include Neolithic and Early Bronze Age (EBA) stone chambered burial ritual monuments (including long cairns, round cairns, barrows and cists), a henge, standing stones and engraved open-air rock art. The Royal Commission for Ancient and Historic Monuments for Scotland (RCAHMS) list over 150 later prehistoric sites within a nine kilometre radius. Engraved rock art is found on or close to burial monuments and as open-air sites on exposed rock outcropping.

The Kilmartin Valley (also known as Kilmartin Glen) is located within the county of Argyll in western Scotland and covers an area of approximately 50 km2 (11 [north-south] x 5 [eastwest] km). It has within its curtilage one of the largest and most complex later prehistoric landscapes in northern Britain. Monuments include Neolithic and Early Bronze Age (EBA) stone chambered burial ritual monuments (including long cairns, round cairns, barrows and cists), a henge, standing stones and engraved open-air rock art. The Royal Commission for Ancient and Historic Monuments for Scotland (RCAHMS) list over 150 later prehistoric sites within a nine kilometre radius. Engraved rock art is found on or close to burial monuments and as open-air sites on exposed rock outcropping.In 2013, a team of archaeologists from the Welsh Rock Art Organisation (WRAO) began a study on the Later Prehistoric sites that contained rock art in western and northern Britain. This study followed an earlier research project which concentrated on a corpus of open-air sites. One of the areas included within this study was Kilmartin Valley.

This paper assesses and discusses some of the findings of this project, suggesting that rock art provided a ritual link between monument and landscape. The focus of this paper will be the small but significant assemblage of the Neolithic stone chambered monuments, cists and standings stones that occupy the lower, central and upper sections of the valley, extending from the village of Kilmartin and the rugged foothills in the north to the marsh grassland of Mòine Mhòr in the south.

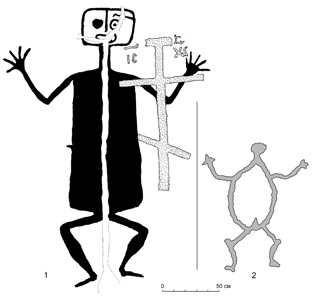

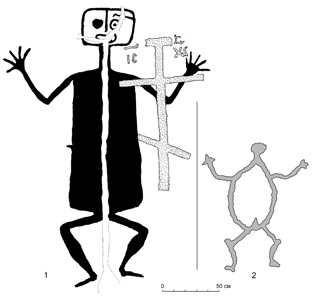

Russian demons by Eugen Kolpakov

A famous demon (“bes” in russian) of the Cape Besov Nos of the Onego Lake is known, probably, to everybody who is concerned about rock art of the Northern Europe. A lot of ideas were written about it and its neighboring figures: fantastic interpretations and exciting discussions about its demonic nature and meaning for the ancient people.

A famous demon (“bes” in russian) of the Cape Besov Nos of the Onego Lake is known, probably, to everybody who is concerned about rock art of the Northern Europe. A lot of ideas were written about it and its neighboring figures: fantastic interpretations and exciting discussions about its demonic nature and meaning for the ancient people.

We’ll cross demon with classic typological method. Formally, the demon is described as follows: a full-face anthropomorphic figure, body of rectangular shape, a rectangular head on a long neck, legs bent at the knees and feet pointing outward in different directions, arms bent at the elbows and forearms are raised up, fingers spread wide. A deep crack passes along the demon on the Besov Nos that divides the body lengthwise into two equal parts, ends in the head, to the sides of the mouth on the spot and left eye (Ravdonikas 1936: Table. 29).

A famous demon (“bes” in russian) of the Cape Besov Nos of the Onego Lake is known, probably, to everybody who is concerned about rock art of the Northern Europe. A lot of ideas were written about it and its neighboring figures: fantastic interpretations and exciting discussions about its demonic nature and meaning for the ancient people.

A famous demon (“bes” in russian) of the Cape Besov Nos of the Onego Lake is known, probably, to everybody who is concerned about rock art of the Northern Europe. A lot of ideas were written about it and its neighboring figures: fantastic interpretations and exciting discussions about its demonic nature and meaning for the ancient people.We’ll cross demon with classic typological method. Formally, the demon is described as follows: a full-face anthropomorphic figure, body of rectangular shape, a rectangular head on a long neck, legs bent at the knees and feet pointing outward in different directions, arms bent at the elbows and forearms are raised up, fingers spread wide. A deep crack passes along the demon on the Besov Nos that divides the body lengthwise into two equal parts, ends in the head, to the sides of the mouth on the spot and left eye (Ravdonikas 1936: Table. 29).

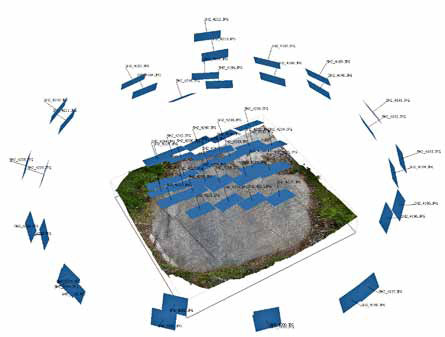

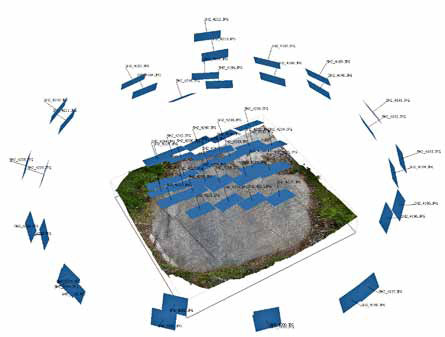

Structure from Motion as documentation technique for Rock Art by Ellen Meijer

Structure from Motion (SfM) is an user-friendly, low budget way of creating three dimensional image-Based Models from two dimensional photographs. The method has found its way into the documentation of rock art in recent years. In Sweden, the application on rock art has been developed by the Swedish Rock Art Research Archives (SHFA), primarily in Tanums World Heritage Area. The pilot project, commissioned by Länsstyrelse Väst, at Aspeberget was very succesful. It is a non-invasive, objective documentation method that is relatively easy to apply in the field that has the potential to become the standard in rock art documentation in the future.

Structure from Motion (SfM) is an user-friendly, low budget way of creating three dimensional image-Based Models from two dimensional photographs. The method has found its way into the documentation of rock art in recent years. In Sweden, the application on rock art has been developed by the Swedish Rock Art Research Archives (SHFA), primarily in Tanums World Heritage Area. The pilot project, commissioned by Länsstyrelse Väst, at Aspeberget was very succesful. It is a non-invasive, objective documentation method that is relatively easy to apply in the field that has the potential to become the standard in rock art documentation in the future.

The name of the technique – Structure from Motion – basically explains its principle: to photograph a fixed object (structure) through movement (motion). The tools needed are a digital SLR camera, a computer and a program to process the photographs.

Structure from Motion (SfM) is an user-friendly, low budget way of creating three dimensional image-Based Models from two dimensional photographs. The method has found its way into the documentation of rock art in recent years. In Sweden, the application on rock art has been developed by the Swedish Rock Art Research Archives (SHFA), primarily in Tanums World Heritage Area. The pilot project, commissioned by Länsstyrelse Väst, at Aspeberget was very succesful. It is a non-invasive, objective documentation method that is relatively easy to apply in the field that has the potential to become the standard in rock art documentation in the future.

Structure from Motion (SfM) is an user-friendly, low budget way of creating three dimensional image-Based Models from two dimensional photographs. The method has found its way into the documentation of rock art in recent years. In Sweden, the application on rock art has been developed by the Swedish Rock Art Research Archives (SHFA), primarily in Tanums World Heritage Area. The pilot project, commissioned by Länsstyrelse Väst, at Aspeberget was very succesful. It is a non-invasive, objective documentation method that is relatively easy to apply in the field that has the potential to become the standard in rock art documentation in the future.The name of the technique – Structure from Motion – basically explains its principle: to photograph a fixed object (structure) through movement (motion). The tools needed are a digital SLR camera, a computer and a program to process the photographs.

The Bru na Boinne. The great passage cairns and prehistori art of the Boyne Valley by Jack Roberts

Ireland is uniquely endowed with an incredibly rich inventory of archaeological and historical monuments and especially those from the earlier prehistoric periods. Sites that date to the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age periods are particularly well represented, most notably in the form of megalithic structures of many kinds. There are also areas in which the tapestry of their daily lives, their habitation sites and field systems survive, from which it can be seen that the later period of the Neolithic, roughly between six and five thousand years ago, saw enormous developments, culturally and economically, a high point of Ireland’s early cultural history.

Ireland is uniquely endowed with an incredibly rich inventory of archaeological and historical monuments and especially those from the earlier prehistoric periods. Sites that date to the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age periods are particularly well represented, most notably in the form of megalithic structures of many kinds. There are also areas in which the tapestry of their daily lives, their habitation sites and field systems survive, from which it can be seen that the later period of the Neolithic, roughly between six and five thousand years ago, saw enormous developments, culturally and economically, a high point of Ireland’s early cultural history.

There is much in the archaeological record to support this view but the main evidence for their being well organized and developed societies inhabiting theland during this time is the great Neolithic passage tomb complex that lies within the area known as the Boyne Valley or Brú na Boinne, Ireland’s valley of the gods. For the ancient Irish, this was their most sacred ground.

Ireland is uniquely endowed with an incredibly rich inventory of archaeological and historical monuments and especially those from the earlier prehistoric periods. Sites that date to the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age periods are particularly well represented, most notably in the form of megalithic structures of many kinds. There are also areas in which the tapestry of their daily lives, their habitation sites and field systems survive, from which it can be seen that the later period of the Neolithic, roughly between six and five thousand years ago, saw enormous developments, culturally and economically, a high point of Ireland’s early cultural history.

Ireland is uniquely endowed with an incredibly rich inventory of archaeological and historical monuments and especially those from the earlier prehistoric periods. Sites that date to the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age periods are particularly well represented, most notably in the form of megalithic structures of many kinds. There are also areas in which the tapestry of their daily lives, their habitation sites and field systems survive, from which it can be seen that the later period of the Neolithic, roughly between six and five thousand years ago, saw enormous developments, culturally and economically, a high point of Ireland’s early cultural history.There is much in the archaeological record to support this view but the main evidence for their being well organized and developed societies inhabiting theland during this time is the great Neolithic passage tomb complex that lies within the area known as the Boyne Valley or Brú na Boinne, Ireland’s valley of the gods. For the ancient Irish, this was their most sacred ground.

The Egtved Girl by Louise Felding

Travel, Trade & Alliances In The Bronze Age.

Travel, Trade & Alliances In The Bronze Age.

The Egtved Girl was buried in Egtved, Denmark 1370 BC. Famous for her well-preserved grave, she has become an icon for the Danish Bronze Age and the object of continuous archaeological study. The latest groundbreaking research has revealed that the she was not local from the Egtved area but instead grew up far from present day Denmark, and travelled long distances in her short life. The Egtved Girl is thus directly linked to the trade and alliance networks that existed across Europe and the Middle East in the Bronze Age. This article wishes to sum up the Egtved Girl’s fascinating story and bring new perspectives to understanding her identity and social role in the Bronze Age.

Travel, Trade & Alliances In The Bronze Age.

Travel, Trade & Alliances In The Bronze Age.The Egtved Girl was buried in Egtved, Denmark 1370 BC. Famous for her well-preserved grave, she has become an icon for the Danish Bronze Age and the object of continuous archaeological study. The latest groundbreaking research has revealed that the she was not local from the Egtved area but instead grew up far from present day Denmark, and travelled long distances in her short life. The Egtved Girl is thus directly linked to the trade and alliance networks that existed across Europe and the Middle East in the Bronze Age. This article wishes to sum up the Egtved Girl’s fascinating story and bring new perspectives to understanding her identity and social role in the Bronze Age.

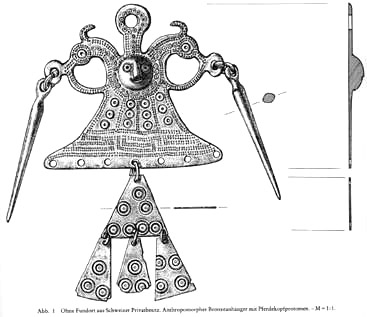

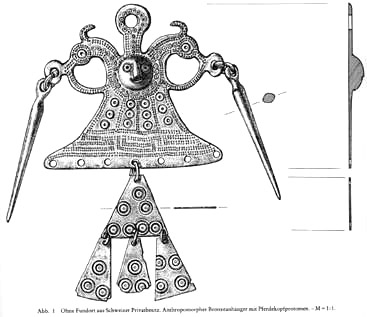

Where have all the young girls gone? by Jeanette Varberg

New studies of rock art show that women in the Swedish rock carvings, believed to have been curiously absent, might have been there all along. However, as they were standing next to chariots, or with hanging phallus, researchers thought the figures to be male warriors.

New studies of rock art show that women in the Swedish rock carvings, believed to have been curiously absent, might have been there all along. However, as they were standing next to chariots, or with hanging phallus, researchers thought the figures to be male warriors.

This article discusses Bronze Age social identities and their role in prehistoric religion and society according to social agencies, materiality and communication with anthropomorphic gods, based on pictorial scenes from Scandinavian rock art and Central European ceramics, bronze figures and finally ancient myths.

New studies of rock art show that women in the Swedish rock carvings, believed to have been curiously absent, might have been there all along. However, as they were standing next to chariots, or with hanging phallus, researchers thought the figures to be male warriors.

New studies of rock art show that women in the Swedish rock carvings, believed to have been curiously absent, might have been there all along. However, as they were standing next to chariots, or with hanging phallus, researchers thought the figures to be male warriors.This article discusses Bronze Age social identities and their role in prehistoric religion and society according to social agencies, materiality and communication with anthropomorphic gods, based on pictorial scenes from Scandinavian rock art and Central European ceramics, bronze figures and finally ancient myths.

|